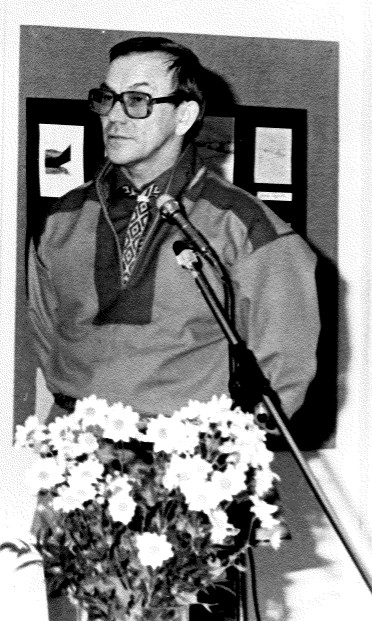

In memory of Culture Aslak

Aslak Niittyvuopio, who died on October 21 was also known as "Culture Aslak." He, if anyone, was a Saame dedicated to defending the true Saame heritage. He was born in 1933, when the landscape of his childhood and youth on the Upper Teno (Ylä-Teno) region lay amid roadless horizons. So he, if anyone, understood how a changing world might threaten the Saame way of life unless external forces were faced in time.

Aslak began working with Saame affairs even during his military service (1952-53) when he read the news in Saame on the radio. He also had a long "career" in teaching, first at Kankaanpää and then during the early 1980s at Utsjoki and at Outakoski. He held a deep affection for music, particularly religious music, studying as a cantor, in which capacity he served until retirement age. This work led him to translate a number of hymns into the Saametongue and he was a member of the hymn book reform committee.

He stressed in numerous conversations with me that it was important to the Saame identity that it should be based on a cultural entirety that rested on historical tradition, a distinct language, and basic, shared Saame values. Aslak's endeavours to honour those Saame values shone through everything he did, including his museum work, his hobbies, his clan activities, Saame politics and so on. He believed that it was wrong to imagine that the Saame people had no identity or awareness of their own sense of self and community long before the current rise of Saame ideals. He was well aware that the roots of the Saamelanguage, which form an essential part of that Saame identity, stretch far back into prehistory. He frequently reminded us of this during the editorial meetings of Sapmelas magazine.

Through their own experiences, Aslak and his kinsman Nilla Outakoski understood the significance of Saame roots and generational continuity for the Saame national identity. The pair opened up ways to influence that identity and worked to reinforce it, including founding Deanu Kultur and Musea Searvin, which traced the sacred Saame sites in the Upper Tenoregion. Thus their work brought Saame values and their protection to the fore, for example in the discussions around the protection of Sulaoja. A fundamental part of this included the bringing together of the history of the Upper Teno region, the revitalisaton of the culture on the basis of common language and traditions and the reinforcement of education and self esteem among the Saame people.

Aslak's work was always grounded in the facts relating to Saame daily life and experience and the way the people perceived their environment. His work acknowledged the beliefs, hopes and needs of ordinary Saame folk. His own Saame-ness drew on his immeddiate social circle and the daily practices of the ordinary Saame individual. He had a remarkable ability to understand and find in the past parallels with the present day. Only a person with his kind of personal experience with another age can achieve that, which marks out the historical professional from the amateur.

Aslak's understanding of the imperative of safeguarding the Saame culture for the Saame people was based on his own experience and a solid foundation in actual history. He wached over a constant yet gradual expansion of awareness for the Saame people, in which Aslak himself was remarkably active. The awakening of the Saame people can thus be seen as a natural growth, during which Saame consciousness only strengthened. His work remains as a beacon of Saame history which lights the way for the rest of us to carry on the work he started, for safeguarding Saame culture in its many forms.